Some days are weirder than others in this line of work.

“Would you like to hold a human brain?” asked Megan Witbracht, associate education director at UC Irvine’s Institute for Memory Impairments and Neurological Disorders (UCI MIND).

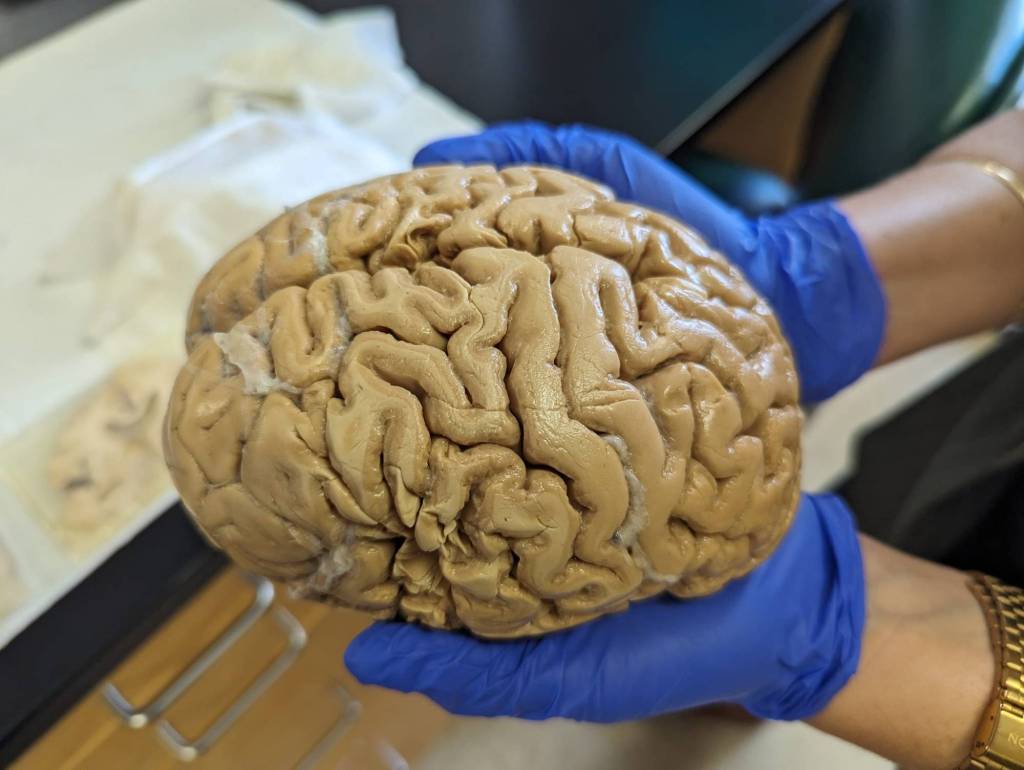

There it sat, on the lab counter. It once belonged to a woman in her 70s. This is where it all happened — love, hate, compassion, jealousy, the punch lines to jokes, the sting of regret. It was way larger than “put your two fists together and that’s the size of your brain” estimates we got in biology class. My mouth hung open as she scooped the big brain into her blue-gloved hands, then gently placed it into my blue-gloved hands.

Let me tell you, the human brain is heavy. Like, four cans of black beans heavy. She had just rinsed it, so it was a bit drippy. Felt sort of rubbery, like dolphin skin.

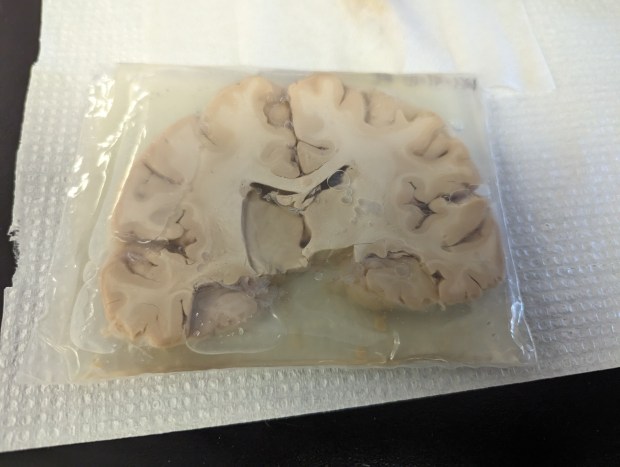

This, Witbracht, explained, is a healthy brain. If you cut this brain into slices, it would look like this, she explained — directing my gaze to a Ziploc-type baggie holding a cross-section of healthy tissue. No holes.

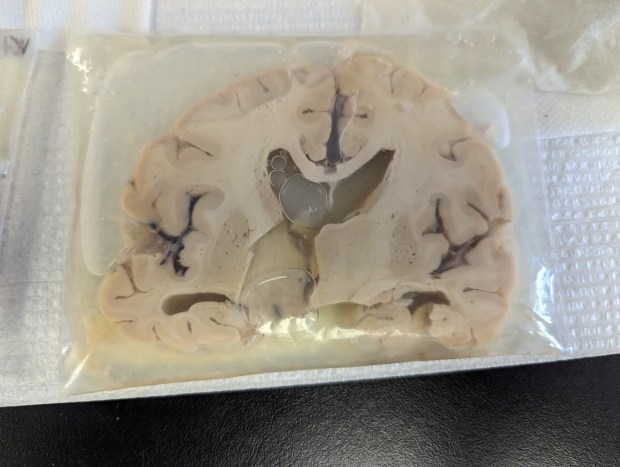

Then she pointed to the other bag. This was a cross-section of diseased brain tissue. It had a gaping, U-shaped cavity at its center, and smaller cavities scattered throughout.

Why do some brains remain robust as time marches on, while others wither? What can be done to halt deterioration in its tracks, or even better — reverse it?

That’s the mystery that decades of work at UCI and other federal research centers are dedicated to unraveling. Some of the biggest brains in science are devoted to understanding aging, dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

“We try not to just be a place where important things are happening, but where people come to get answers and understand what is real and what isn’t,” said Joshua Grill, director of UCI MIND. “There’s a lot of garbage out there.”

Millions upon millions of dollars are pouring into Alzheimer’s research, new drugs are coming online, “and…

Read the full article here