BY BYRHONDA LYONS

Each day someone at Patton State Hospital near Highland handed Fredreaka Jack her medication: three pills to manage her schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, one or two for her blood sugar, one for hypertension and one for hypothyroidism.

That all changed on April 14, 2022. Jack had been sentenced to 32 months in prison after pleading guilty to second-degree burglary. After successfully petitioning to be paroled into the community, she just had to complete about three months at a state-funded reentry facility in El Monte known as Walden House and she’d be free.

Jack told her mother she loved the facility and the hints of freedom it offered — trips to the store, access to her phone and the small job she had helping out. She hoped to be reunited with her family in Louisiana soon.

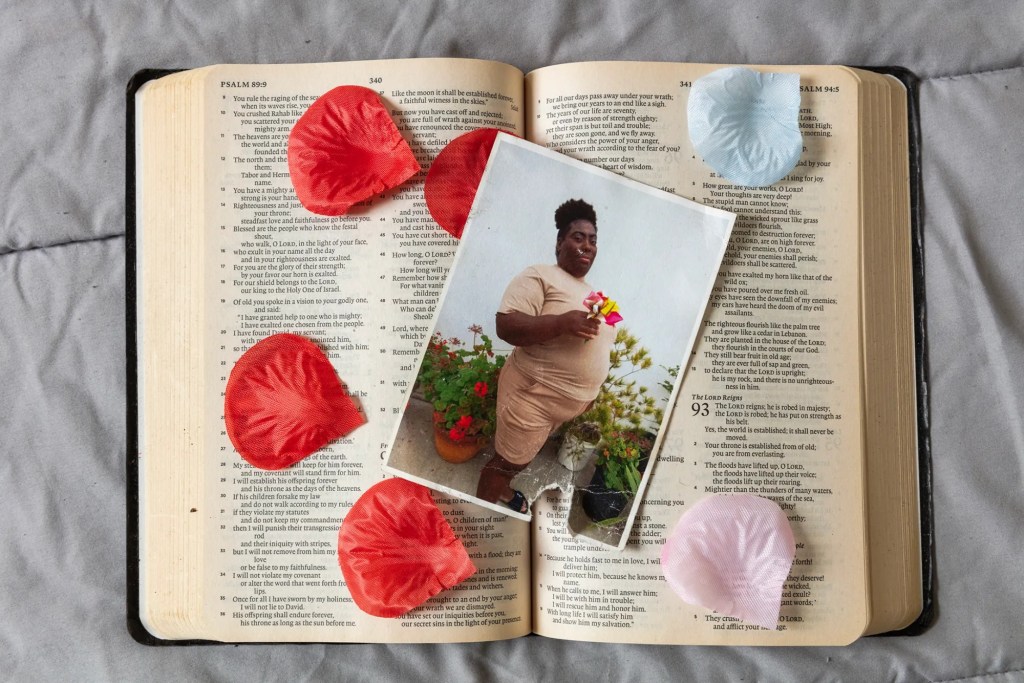

Instead, Jack would be dead within months. She was 37.

In granting her the freedom she sought, the court released Jack into a public parole system so full of holes that Jack’s death was almost preordained, a review of thousands of pages of medical records and court documents reveals.

Jack was battling serious mental illness and coming off nearly a decade and a half of institutionalization. A psychologist for the state hospital warned that she “remains a danger” and was “psychiatrically and behaviorally unstable.” The Board of Parole Hearings denied Jack’s request to be freed.

Yet, after she appealed, a San Bernardino court released her from the state hospital’s care, meaning she couldn’t enter its outpatient program for people with mental illness. Instead, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation sent Jack into a home focused on substance abuse to serve her parole.

RELATED: Newsom approves housing homeless at San Bernardino County’s Patton State Hospital

Left by state policy to navigate the complex mental and physical health care system on her own, Jack failed at nearly every turn. So did California’s parole system – and…

Read the full article here