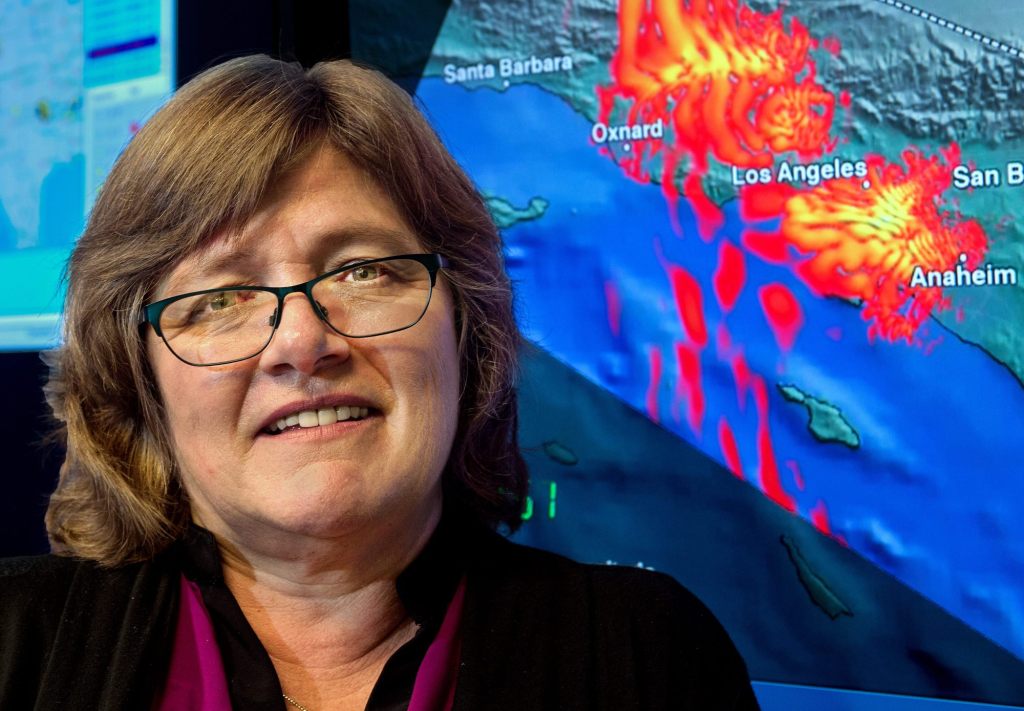

For decades, world-renowned seismologist Lucy Jones has pored over earthquake data and made recommendations to policymakers about how communities could better prepare for the Big One.

In some respects, Jones believes, Southern Californians are better off today than 30 years ago when the 6.7-magnitude Northridge earthquake jolted many Angelenos out of bed in the early morning hours of Jan. 17, 1994.

That quake, the costliest in U.S. history, killed dozens of people – 72 are believed to have died, including from heart attacks — while about 9,000 people were injured. The quake buckled freeways and left billions of dollars in damage to homes, businesses, hospitals, parks, roadways and utilities. One estimate placed the damage at $25 billion.

After the destructive temblor, the state adopted new building codes which Jones called a “significant improvement” over previous standards.

Along with that, “in the past decade, we’ve accomplished quite a bit in earthquake retrofitting,” she said during an interview this month. “Those are going to make a really big difference.”

But while the state’s building codes prevent structures from collapsing – thereby saving lives – the standards aren’t high enough to prevent damage, Jones said. In other words, in a big enough earthquake, a structure may not completely crumble, but there could be enough damage that it would have to demolished.

And when buildings or infrastructure are badly damaged, that could mean not being able to return to a home or office, not having access to power or water, or being cut off from roadways or transportation systems – scenarios that could spell catastrophe for a neighborhood or the local economy and stymie recovery efforts.

“We’ve done a very good job about reducing the life risks — but not about the financial risks” of earthquakes, Jones said.

In 2016 she founded the Dr. Lucy Jones Center for Science and Society in Southern California after retiring from the…

Read the full article here