If you or someone you know is in need of help, dial 988 for the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline for free and confidential support or text HELLO to 741741 for the Crisis Text Line.

Nada Hassanein | (TNS) Stateline.org

When she tried to find help for her daughter’s depression, Michelle Romero was frantic, panicked and heartbroken. She searched and searched for mental health clinicians within her daughter’s insurance coverage network.

But the Houston-area mom of three couldn’t find a psychiatrist nor a psychotherapist who accepted her daughter’s health insurance and was close enough to the family’s neighborhood, she said. In her network, one clinician had closed their practice. Another was at capacity with patients.

So, each week, the family paid about $300 out of pocket for their daughter’s psychotherapy and psychiatry sessions. Romero has maxed out her credit cards.

At Christmastime last year, Romero’s daughter was hospitalized for two weeks. Then 14, she had tried to kill herself. It wasn’t her first attempt: That was when she was a 10-year-old fifth grader.

The family began the new year with a $30,000 hospital bill, of which insurance paid just a portion.

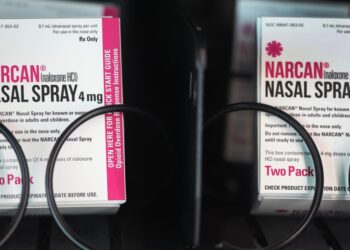

The Biden administration is pushing insurers and state regulators to improve mental health care coverage. The move comes as overdose deaths rise and youth mental health problems grow more rampant, disproportionately affecting communities of color. Inflation and a shortage of mental health care providers, including psychiatrists and specialists who treat adolescents, further hinder access to care.

“Something needs to change,” Romero said. “There are too many people who need help. And there’s not enough doctors.” Insurers, she said, “need to do better.”

The federal Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, enacted in 2008, doesn’t require insurance plans to offer mental health coverage — but if they do, the benefits must be equal with coverage for other health conditions….

Read the full article here