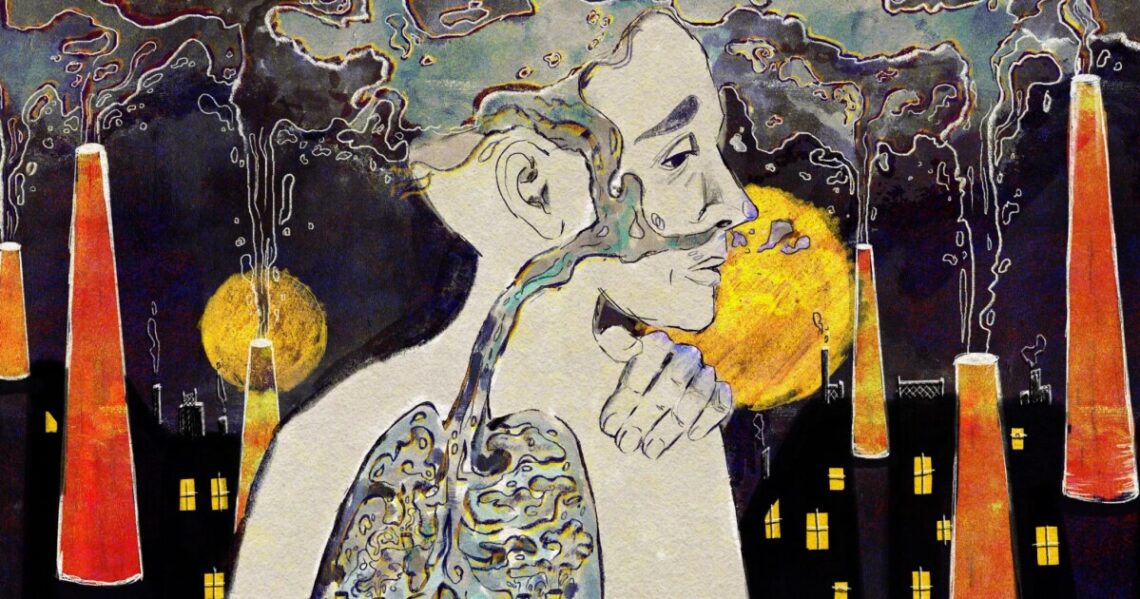

In the 1990s, residents of Mexico City noticed their dogs acting strangely — some didn’t recognize their owners, and the animals’ sleep patterns had changed.

At the time, the sprawling, mountain-ringed city of more than 15 million people was known as the most polluted in the world, with a thick, constant haze of fossil fuel pollution trapped by thermal inversions.

In 2002, toxicologist and neuropathologist Lilian Calderón-Garcidueñas, who is affiliated with both Universidad del Valle de México in Mexico City and the University of Montana, examined brain tissue from 40 dogs that had lived in the city and 40 others from a nearby rural area with cleaner air. She discovered the brains of the city dogs showed signs of neurodegeneration while the rural dogs had far healthier brains.

Calderón-Garcidueñas went on to study the brains of 203 human residents of Mexico City, only one of which did not show signs of neurodegeneration. That led to the conclusion that chronic exposure to air pollution can negatively affect people’s olfactory systems at a young age and may make them more susceptible to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

The pollutant that plays the “big role” is particulate matter, said Calderón-Garcidueñas. “Not the big ones, but the tiny ones that can cross barriers. We can detect nanoparticles inside neurons, inside glial cells, inside epithelial cells. We also see things that shouldn’t be there at all — titanium, iron, and copper.”

The work the Mexican scientist is doing is feeding a burgeoning body of evidence that shows breathing polluted air not only causes heart and lung damage but also neurodegeneration and mental health problems.

It’s well established that air pollution takes a serious…

Read the full article here