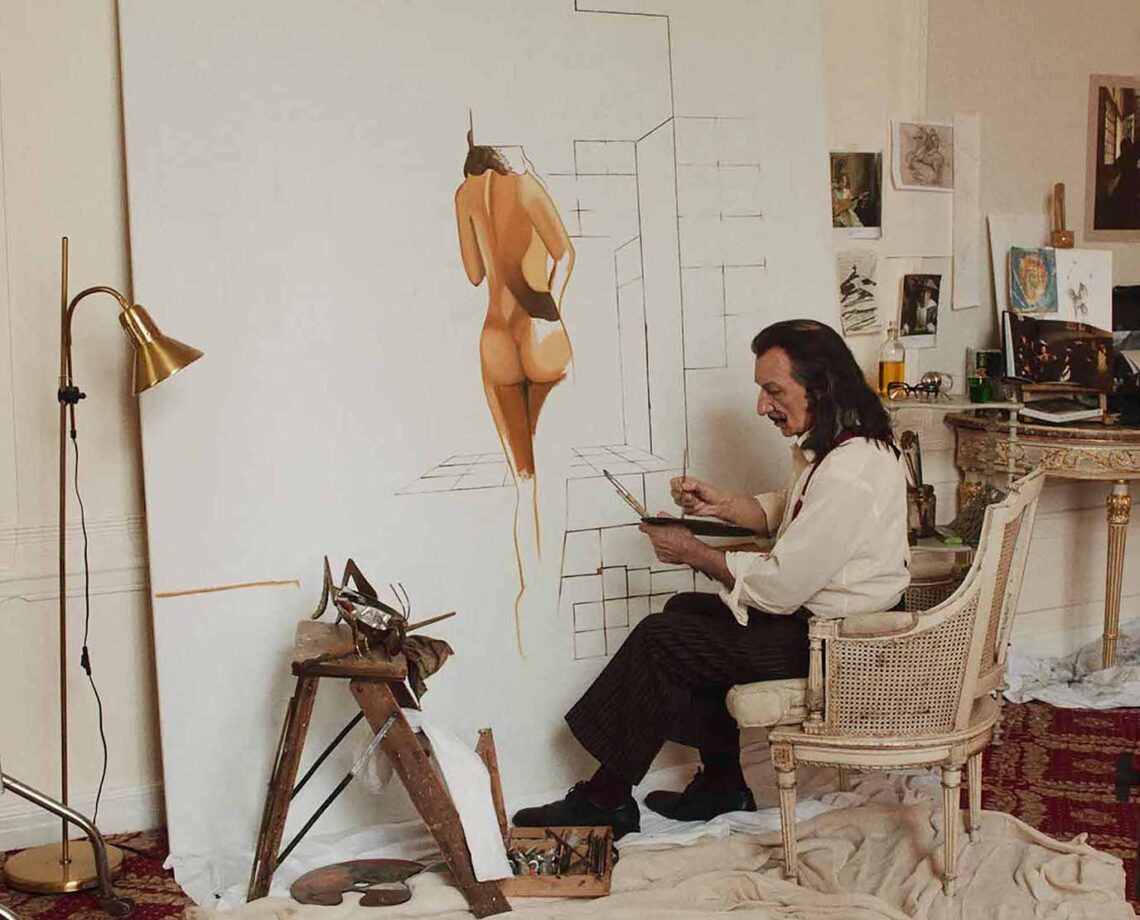

Mary Harron’s Daliland struggles to find itself, amid a predictable arsenal of biopic cliches and actor-y impersonations. Given the deliberate outrageousness that infused everything about Salvador Dali, from his performance-art-ish public stunts to his six-decade career of sui generis art-making, you’d think there’d be a movie to be made about him. But maybe there isn’t — biopics are a tricky business, dizzy with mere celebrity and often starved for dramatic justification, and if your subject was world-famous, successful, and didn’t die tragically young, there won’t be a helluva lot of protein in your trail mix. Dali was a wildly effective self-promoter and eccentric hedonist as well as a spectacularly gifted image-maker, all the way up to a few years before he died, and the only dilemma he seemed to face was that he, and the in-vogue-ness of his art, couldn’t last forever. It’s a life — one that must have been a champagne-gassed roller-coaster limo ride, certainly — but not a story.

The focus is on the ’70s, with a past-his-prime Dali (Ben Kingsley) holed up in New York’s St. Regis Hotel, throwing shindigs when he’s supposed to be grinding out paintings for an upcoming show. The historical moment is referenced lightly: The art world has passed Dali and surrealism by, in favor of abstraction, pop art, etc. Our entry into the artist’s hermetic little Gomorrah is a fictional innocent, James (Christopher Briney), a budding artist working for Dali’s gallerist who is in no time assigned to assist the splenetic master, and to report back on his progress. The invention of screenwriter John C. Walsh (Mr. Harron), James is a cipher, as these naive eyes-and-ears characters tend to be; the supposedly wild lifestyle he is privy to amounts to flashy hangers-on parties, with Kingsley’s showman holding forth to some acolytes (including Alice Cooper, played forgettably by Mark McKenna) while booze is guzzled and boobs are haphazardly exposed….

Read the full article here