BURLINGTON, Vt. — “You can’t inject a horse tranquilizer and think nothing bad is gonna happen” to you, said Ty Sears, 33, a longtime drug user now in recovery.

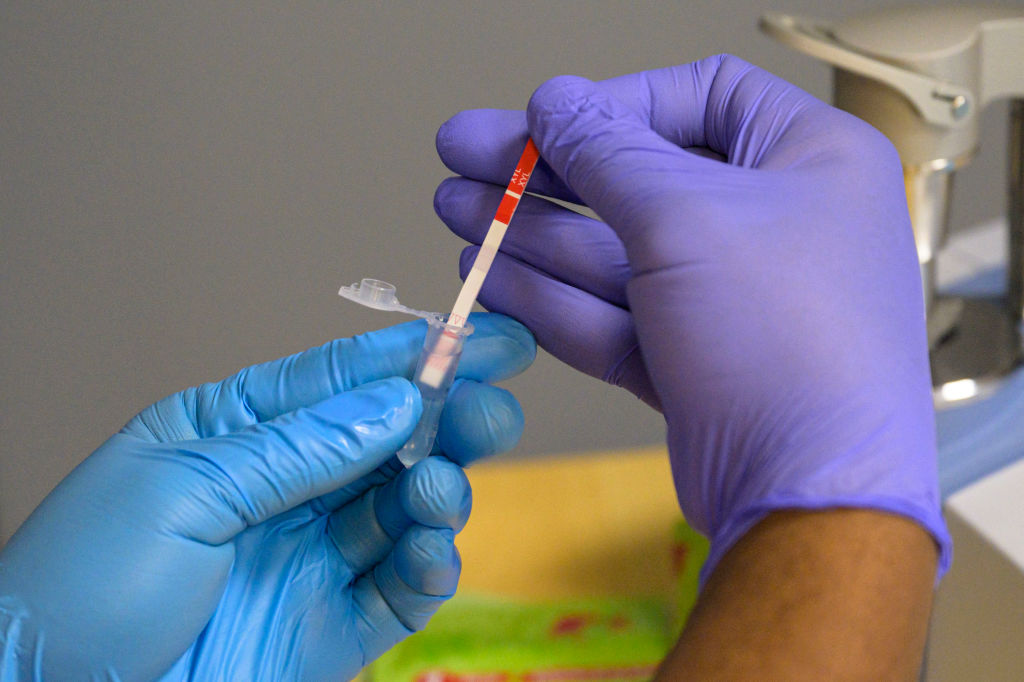

Sears was referring to xylazine, a sedative used for animal surgeries that has infiltrated the illicit drug supply across the country, contributing to a steady climb in overdose deaths.

Sears divides his time between Burlington and Morrisville, a village an hour to the east. In Burlington, he visits clusters of drug users, offering water, food, and encouragement.

He has been there, been down, done time, struggled to adhere to treatment regimens. But this, he said, is different: first, fentanyl — estimated to be 50 to 100 times as potent as morphine — and now xylazine, and the life-threatening wounds and sores it can cause.

Sears implores those he encounters who suffer the effects of these drugs to look at what they’re doing to themselves. But to little avail.

“They say they’re unable to get out of it — that they don’t have a plan to get out of it.”

Worse, those who seek help breaking their addictions face treatment options rendered less effective by the prevalence of fentanyl, xylazine, and other synthetic drugs. Vermont’s pioneering efforts in establishing a statewide program for medication for opioid use disorder, known as Hub and Spoke, now face significant new challenges.

Launched in 2012, Hub and Spoke put prescription medicines at the center of the treatment strategy, which many addiction specialists say is the most effective approach. Vermont offers methadone treatment at regional hub sites for those with the most intense needs, while smaller community clinics and doctors’ offices — the “spokes” — provide care such as dispensing the opioid withdrawal drug buprenorphine.

Advocates and experts in Vermont honed the model, and today hub-and-spoke systems or variations are in place nationwide, including in

Read the full article here