Rick Jaenisch went through treatment six times before his hepatitis C was cured in 2017. Each time his doctors recommended a different combination of drugs, his insurer denied the initial request before eventually approving it. This sometimes delayed his care for months, even after he developed end-stage liver disease and was awaiting a liver transplant.

“At that point, treatment should be very easy to access,” said Jaenisch, now 37 and the director of outreach and education at Open Biopharma Research and Training Institute, a nonprofit group in Carlsbad, California. “I’m the person that treatment should be ideal for.”

But it was never easy. Jaenisch was diagnosed in 1999 at age 12, after his dad took him to a San Diego hospital because Jaenisch showed him that his urine was brown, a sign there was blood in it. Doctors determined that he likely got the disease at birth from his mom, a former dental surgical assistant who learned she had the virus only after her son’s diagnosis.

People infected with the viral disease, which is typically passed through blood contact, are often outwardly fine for years. An estimated 40% of the more than 2 million people in the U.S. who are infected don’t even know they have it, while the virus may quietly be damaging their liver, causing scarring, liver failure, or liver cancer.

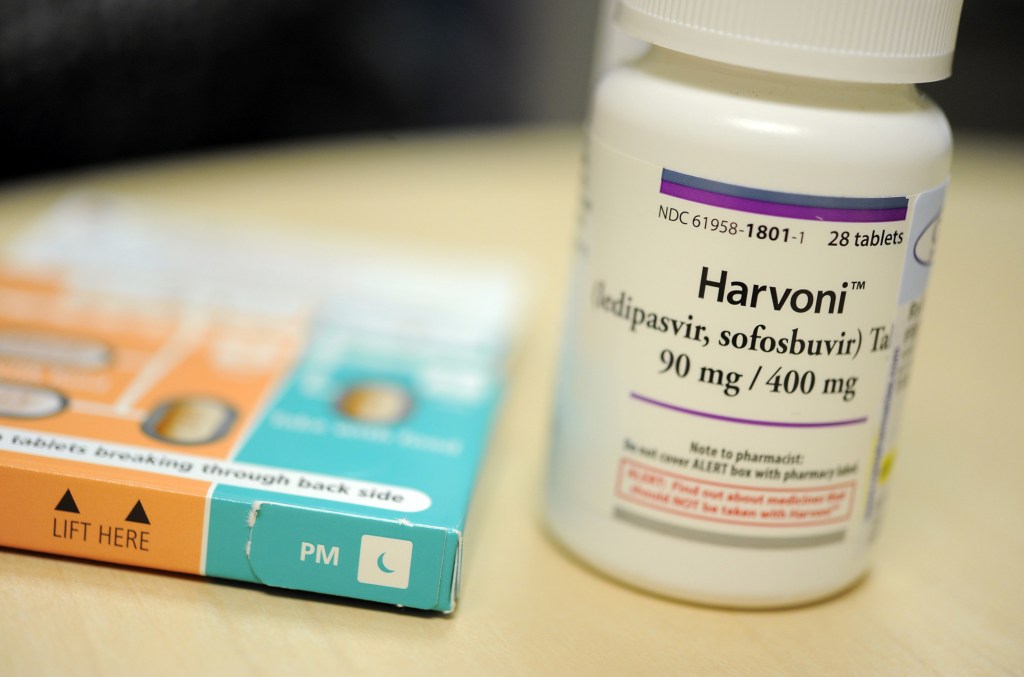

With several highly effective, lower-cost treatments now on the market, one might expect that nearly everyone who knows they have hepatitis C would get cured. But a study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published in June found that is far from the case. A proposal by the Biden administration to eliminate the disease in five years aims to change that.

Overall, the agency’s analysis found, during the decade after the introduction of the new antiviral treatments, only about a third of the people with an initial hepatitis C diagnosis cleared the virus, either through treatment or…

Read the full article here